I studied English Literature at university and I didn't write a line of code until I was 24. Since making the fateful decision to learn to code, I've been a front-end developer, backend software engineer (of varying levels of seniority), machine learning engineer, tech lead, and engineering manager. I also teach over 10,000 students online about machine learning engineering. I made the transition without going back to school, and without spending thousands of dollars on a bootcamp.

This post explains how to approach learning to code for about the price of a sofa.

There are so many "learn how to code" articles that miss all the important parts and will leave you confused. This is a long-form guide that will help you to navigate the bewildering array of different advice and which will provide a methodology to sift the information you receive along the way.

Crucially, the advice here is a far safer route, allowing you to explore programming without quitting your current job/major, or making any kind of significant financial commitment. This matters because you need plenty of time to determine if coding is right for you (more on this soon).

Contents

- Part 1: What Is Coding and Why Learn it?

- Part 2: Mindset When Learning How to Code

- Part 3: Why Bootcamps Are a Terrible Idea (And What You Should Do Instead)

- Part 4: Picking Your First Programming Language

- Part 5: Project-Based Learning

- Part 6: Building Your Network

- Part 7: Getting Your First Job

- Part 8: Keep Growing and Getting Promoted

Part 1: What Is Coding and Why Learn it?

Coding is automating stuff with computers. Some view it as an art, a kind of craftsmanship. Others look at it as churning out widgets. The truth is that it is a tool, like a paintbrush, which you can use to do routine things like painting a white wall, or with which you can paint the Sistene Chapel.

The Opportunity

There are three key reasons why you might want to learn to code:

- To get better at your current job

- To start a new career as a software engineer

- To give you the skills necessary to launch a product or passion project of your own

There is a lot of overlap in the learning steps for each of these paths, and this guide is applicable for any.

Getting Better at Your Current Job

In today's market, an analyst who can crunch data beyond Excel is going to be able to do more. A doctor who understands APIs is worth their weight in gold. A lawyer who can write a chatbot so you don't have to pay parking tickets... you get the idea. Stacking skills is something that Scott Adams has talked about at length: if you can get quite good at two or three different skills then you rapidly become a rare commodity. This is a great way to build what Cal Newport calls career capital which will unlock more options in your career, which means a greater chance at fulfilling work, autonomy and good stuff like that.

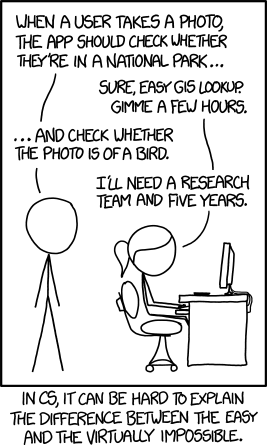

Even if you have no intention of becoming a professional software engineer, understanding the steps involved in coding, the challenges and having a sense of what is trivial and what is ludicrously hard, will serve you very well in roles such as product management, project management, leadership, design, and sales.

source: https://xkcd.com/1425/

Starting a New Career

Software engineering in the western world can be an attractive career option (depending on whether you enjoy problem-solving - more on this in the next section). Here are the reasons in favor of it:

- It is generally quite well paid (more on this in part 8 on growing your career)

- It is easy to change industries

- For now, the market dynamics tend to be in your favor (shortage of supply) meaning that once you are competent it is very easy to find a new job, and you have to put up with less BS from managers (e.g. refusing vacation requests, forcing you to work crazy hours).

- The work can be incredibly interesting (highly dependant on the company and the project).

- If you are a bottom-of-the-ladder engineer you can avoid having to go to many meetings (unless you work in consulting, which probably warrants its own post).

Launching Your Own Product

Some people just want to launch their own product or create open-source software.

Wanting to build a product is what got me into software development. It was my source of motivation.

Some people just want to launch their own product or create open-source software.

Wanting to build a product is what got me into software development. It was my source of motivation.

It's quite a different mindset to those people who view programming as simply a profession. This is all about code as a tool to bring a product or service into reality. This can be incredibly powerful because:

- It allows you to generate alternative income streams

- You can reach millions of people

- Building products means that you are no longer selling your time for money, which is the route to freedom as is best described by Naval Ravikant in this clickbaity-sounding but excellent podcast

- Even if you are not a professional, it will allow you to determine if someone else is competent which means that you can hire/enlist other, more experienced developers to help you without getting ripped off or hiring someone who is an idiot (which is a great way to tank your startup).

An example of someone like this is Jonathan Pyle, the creator of doccassemble who is an attorney who self-taught over many years to create what is a very impressive software product used by large numbers of businesses.

Another way to phrase this is that learning to code gives you a lot of leverage in the form of tools you can use to automate tasks and processes. You can learn how to spin up servers in a data center on the other side of the planet for a few cents...in effect, you can put yourself in control of an army of robots. A few decades ago this would have required the resources of a major government. Now it just requires you to have some discipline.

The passion project

A subset of launching your own product is tinkering and scratching your own itch. In some cases this can then lead on to more serious or commercial products. Naturally, some people do it just for their own enjoyment and aren't bothered about launching a product.

Terminology

A lot of terms get thrown around when describing computer coding. Terms like:

- Programming (and the job title "Programmer")

- Software Engineering (and the job title "Software Engineer")

- Development (and the job title "Developer")

- Hacking (and "hackers")

I've overheard conversations where someone interrupted to point out: "I am a software engineer, not a developer".

The truth is, it barely matters. People on the website Hacker News love to argue until they're blue in the face about ideas like "a software engineer usually received formal training at university" or "a hacker follows a certain ethos". Some do, some don't. They can all write code. Move on.

Part 2: Mindset When Learning How to Code

Not everything can be taught, but everything can be learned.

This is a powerful concept, which you should really internalize. Learning is what happens when you do something. You can take a load of classes on programming, but until you start writing your own programs you won't really know how to code.

I would argue that if you ensure you have strong foundations in Math and logic then you can truly learn anything. Even with relatively weak foundations, it is still possible to learn to code well. There is very little in day-to-day software engineering that requires a deep knowledge of Math (this is a common misconception). The complexity comes from the sheer volume of different technologies out there, the size of different systems and their interactions, and from an endless litany of jargon. However, given enough time, this is all stuff that you can pick up even if you only have about Middle-school level Math. It's obviously different if you want to do a PhD in theoretical Computer Science, but that is not necessary to achieve any of the opportunities discussed in the first section.

All this is significantly easier, however, if you cultivate a love of learning. Cultivate might even be the wrong term since children innately possess this love. Formal education, life, and taxes seem to gradually suck this out of adults. So perhaps "rediscover" a love of learning is a better way to put it. Why is this important?

Love of learning and the short-term

Learning to code is deeply frustrating, and it takes a while before you get anywhere

Computers are bloody annoying. They do exactly what you tell them, and nothing else. It is very important to mentally prepare yourself for confusion when you learn to code. Confusion is to be expected and embraced. If you can (quite truthfully) tell yourself that frustration and a certain degree of pain is necessary to progress and learn, and you can take pleasure in the small breakthroughs along the way, you will be much more willing to accept the challenge.

Alternatively, you can embrace Stoicism and just rationalize that you are new to software and therefore you will make a large number of mistakes, but ultimately it is in service of learning, which in turn unlocks the opportunities we have already discussed.

Days will be lost to a missed semi-colon. Weeks will be lost to a fundamental misunderstanding of how a certain technology works. The stories you tell yourself along the way will dictate your ability to continue, and enjoy the process. The mindset piece is the one people are most tempted to skip over ("yeah, yeah, tell me which programming language to learn already"), but it is the foundation.

The sub-genre of general "learning" which coding often (though not always) falls into is "problem-solving".

Love of learning and the long-term

If you continue your learning to code journey beyond the beginner phase - perhaps becoming a professional or running side project of reasonable complexity, then you are signing up for a treadmill of new stuff to learn. In the same way that if you become a professional boxer you are also signing up to be a semi-professional runner, if you sign up to work with software as a professional, you are also signing up to become an autodidact. New languages, new frameworks, new protocols, new algorithms, new infrastructure...the list goes on. Technology moves underneath your feet, and if you only ever stick with one area then you can find your skills out of date. If you never cultivate a love of learning then this treadmill will feel like a painful grind.

Equip Yourself With The Right Tools

We've established that embracing learning (and frustration) is part of the package. What does that actually mean, practically?

Learn How to Learn

First of all, you will want to make sure that you have learned how to learn. Coursera's most popular course is on this very topic, and would encourage everyone to study it. The course is based on the book A Mind for Numbers by Barbara Oakley. I would also supplement this with Scott H. Young's Ultralearning

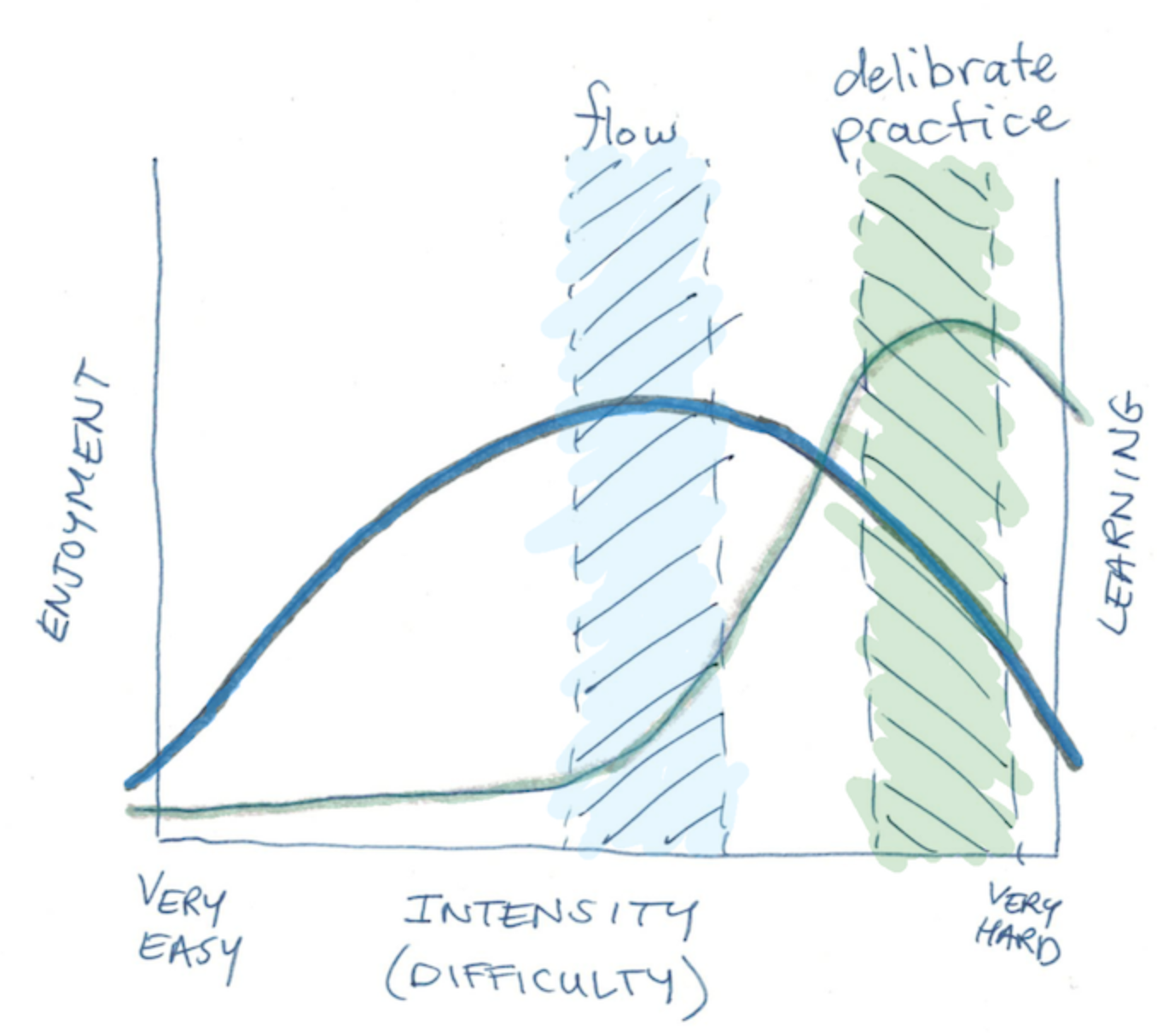

Most people massively overestimate the quality of their learning process. An appreciation for spaced repetition, deliberate practice, and teaching others are adjustments that will compound over a lifetime.

On Reading

Reading books is faster than watching videos or listening to podcasts. Therefore if you don't like to read, the speed with which you will be able to accumulate new information will be slower. I'm not saying it's necessary to be "a reader", but am saying it's better. A favorite quote on this from Naval Ravikant is

Read what you love until you love to read

At the very least, you need to be willing at times to RTFM. So few people do this, and if you are one of them you will soar through the ranks of masses like a goddamn phoenix.

On Doing

Classes, books and courses have an important role to play in your learning journey. But projects are the key. They are so important that this guide has a dedicated section on project selection.

Don't Worry About Credentials

"I haven't got a computer science degree so I can't be a software engineer" is total guff. Yes you can. And it's also possible that you'll be far better programmer than many with those credentials. Some of the best people I've ever worked with were self-taught.

Generally, we as a society care too much about formal education. At the university level, education is just mostly just signaling. Most things you actually need for the job, you learn on the job. Most things about dealing with others and teamwork you could learn by joining a sports team or a drama club instead.

Society is very gradually coming around to this way of thinking. You see this with companies like EY dropping the requirement for a degree for graduate positions.

Job markets are less stable than in the past. You can make yourself stand out by creating your own audience, launching your own apps, and generally exercising your creativity. No one epitomizes this better than Harry Dry and his Kanye West dating app project (Harry knows how to hustle).

Part 3: Why Bootcamps Are a Terrible Idea (And What You Should Do Instead)

A quick Google search will find you plenty of detractors ("total waste of money") and promotors ("changed my life!") for the various bootcamp schools (Lambda School, Hack Reactor, Make School etc.)

A lot of friends have asked me if they should do a bootcamp over the years. The idea of a bootcamp is to teach you enough of the key skills you need to be a software engineer so that you can land a job in a very short period of time (3-9 months), thus enabling a rapid career transformation.

Note that I'm not discussing bootcamps which claim to train you to be ready for an entry-level software engineering job in 6-12 weeks, as this is patently not enough time and such courses are preposterous and will only impart a very superficial understanding of coding topics.

Returning back to the more respectable bootcamps which span 3+ months, my question: Do the benefits of a bootcamp justify the financial risk? Let's dig into these.

Bootcamp Benefits

- Clearly structured curriculum

- Expert instructors

- Classmates who you can practice teamwork with & get a sense of community

- Advice on which projects to pursue

- Advice on CV/interview prep

With the exception of (3), the other four can be pieced together or hired for far less. In this guide, I am going to show you how to do this. Having classmates who you are learning with, and the accompanying social pressure is a bit harder to simulate on your own, but it is doable, and I will talk about substitutes. What this means is that really, what you are paying for is the package. It's having everything thought out and prepared for you. "Learn this, now learn that. Now do this project, now talk to this instructor". Now I definitely agree, there is value to this kind of structure and regimented timeline. But is it worth it? Let's consider the downsides:

Bootcamp Downsides

- The straight cost of the tuition (either upfront or gradually taxed from you once you have a job) which usually lurks somewhere around $20k

- The risk to your career (given that there is no need to take this risk)

- The pressure of full-time learning commitment (and its impact on your judgment)

- The lack of flexibility

- The loss of personal discovery through a prescribed curriculum

For my money, 1 and 3 are the key downsides. (1) is pretty self-explanatory. (3) is all about the key question you actually need to be asking which is: Do I (at least to some degree) enjoy software engineering? This is not some hand-wavy "love what you do" crap. Passion is massively overrated. However, if you actually dislike programming and problem-solving, then you will not have the discipline to continue learning in the long run. But here's the rub: You definitely can't say whether you like it or not until you have written a program of reasonable complexity. It takes time and effort to acquire the necessary level of competence (in any skill) so that you are able to enter a [flow state](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_(psychology) and get a feel for what coding beyond the beginner phase is going to feel like.

If you're worried about money because you have "put all your chips in" and quit your job to do a bootcamp then you're going to be way too stressed to make an accurate judgment call about whether you actually enjoy what you're doing. Embarrassment and social pressure drive much more of our behavior than we would like. Announcing to your friends and family that you will do a bootcamp and then turning around six months and $20k later to say "actually I'm not that into coding after all" is a pretty humiliating thing to go through. All this is to say: Why put yourself through all of this...

...When there is a perfectly viable alternative with none of the downsides which gets you the same result.

I can't resist a final dig at the bootcamp industry: there are now courses to help you get onto bootcamps! Looking forward to the bootcamp bootcamps.

Part 4: Picking Your First Programming Language

I called this section "picking your first language" because it's better for SEO - that's what everyone Googles. In reality, the question you actually want to be asking is: What to learn and when.

Here is a winning template to get you started:

- Pick a language that is easy for you to run on your computer: Javascript, Python, Ruby or maybe Swift are good choices. Just make sure you pick one and stick with it. Don't try and learn more than one at the same time, that is the path to madness.

- Pick up either a good book or online course on that language (not some 700-page tome or 30-hour extravaganza, something that you can read in a week). Pick one with good ratings. Don't overthink it. Note that one of the primary benefits of such a book or course is the section on how to install and get started since setup is one of the main barriers to entry for coding

- Focus just on the basic syntax of the language. Make sure you type everything your course or book asks you to (if it's not asking you to run basic things on your computer, it's a bad book or course)

- As soon as you have the basic language syntax down, switch to projects. Begin the project ratchet sequence - more on this in the next section. How do you know when you know enough basic syntax? It's probably after about 10-20 hours of deliberate practice. If you're still focusing on syntax after that, you're procrastinating.

That's it! That's your first couple of weeks of learning sorted. You can and should be able to do this with a modest time investment evenings and weekends.

Some experienced software engineers will foam at the mouth at my language suggestions above - what about starting with a "real" language like C? Javascript is such a horrible language, don't recommend that! Don't we need to teach people about object-oriented programming with Java? Why not look at functional programming? Blah blah. Shh. What is needed is something easy to setup, with loads of examples and documentation online. There will be time for more languages later (see section 8).

Tools

Start with a simple text editor. Notepad++ is fine. Or sublime text. Worry about a fancy IDE once you reach "Late Stage" projects (more on this in the next section).

Finally, one of the few things I will be prescriptive on is that you need to learn how to use git Even your smallest projects should be kept under version control (and also stored in the cloud through a service such as github or gitlab). This will save you so much pain when you make mistakes and need to bring your code back into an earlier functioning state. Trust me on this one.

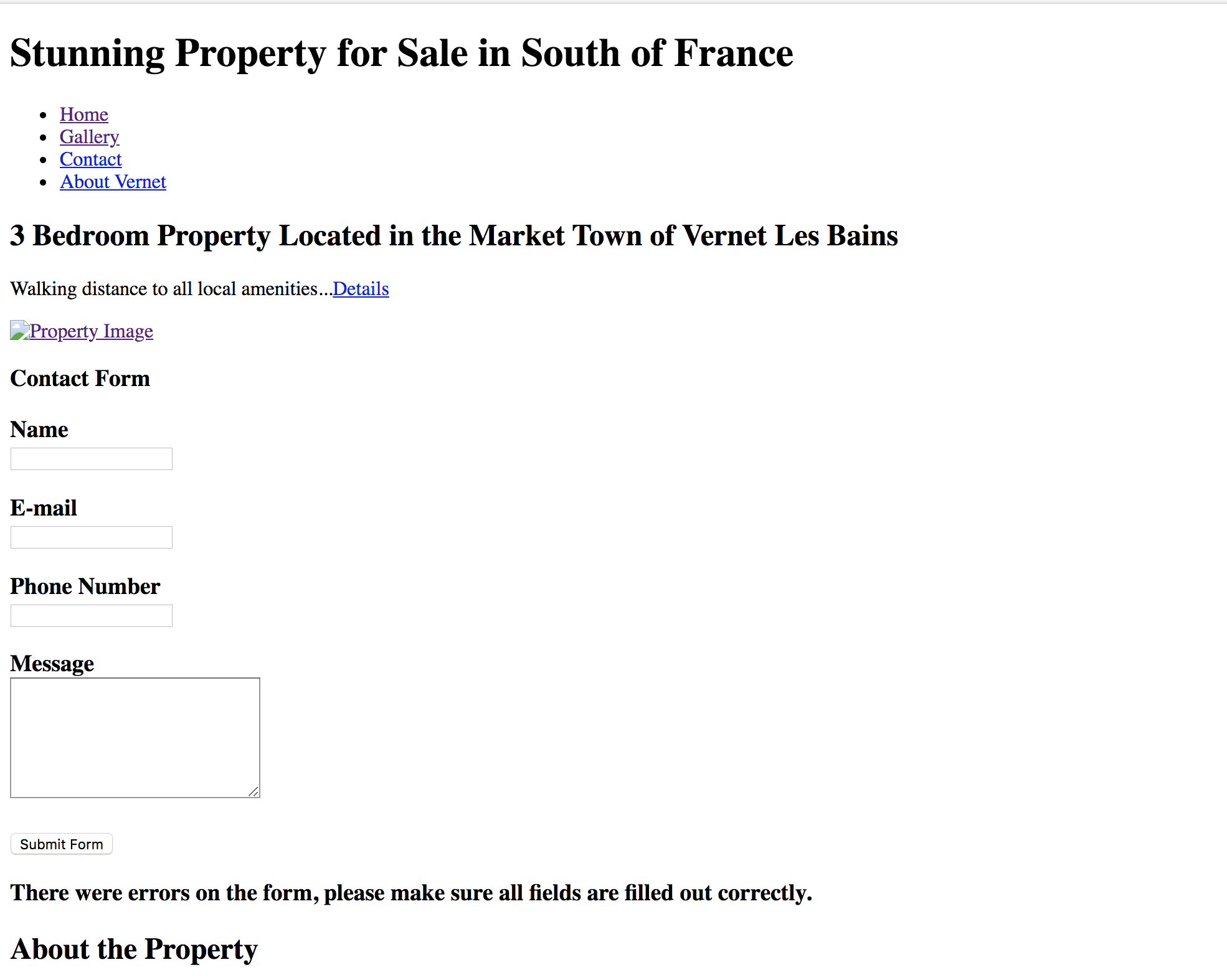

Personal Journey Excerpt

I started with Javascript because I wanted to build a website. If I recall that first project was to build an online raffle site (yeah alright, laugh it up). Needless to say, it wasn't very good. I recall spending about 3 days trying to images and text into a good looking layout on a page (and in the process discovered that HTML involved this weird thing called CSS)

Part 5: Project-Based Learning for Learning to Code

You learn by doing. And you "do" through projects. A project can be as simple as printing "Hello, World!". At the other extreme, a project can be a fully-functioning product that you turn into a business or open-source tool with thousands of users.

For those teaching themselves to code, a key skill to acquire is the art of judging a project's difficulty

You want to choose a project scope and complexity that enhances your learning. This is much harder than it sounds - professional engineers make mistakes in estimating project difficulty and timelines all the time. This is a great post on why software projects tend to take longer than expected Practically, this means always err on the side of "too simple", especially in your first half dozen projects.

How to Choose Your Projects

Early on in your learning journey (first 1-3 months), you want to focus more on "will this help me to learn" with a touch of "will I find this interesting" to keep your interest kindled. As you become more familiar with the basics you can gradually move the emphasis more to projects you find interesting (which typically means greater complexity).

There are two key mistakes early on when it comes to projects:

Risk 1: Choosing A Project That Is Too Hard.

This is the most likely. A friend of mine considering a switch from investment banking to software engineering suggested that he build a trading bot as his first project and I had to bite my knuckle. No! You will fail. You will get discouraged. Don't set yourself up for failure like that.

Risk 2: Pracrastinating from Doing Projects

I'll just do this online course first, or another dozen online coding challenges, or first read this book on Django...these are all unconscious attempts to avoid the feeling of discomfort that comes with projects. Projects are unclear! But this is the point, and this is why there comes a point where you must leave the warm embrace of the online course and enter the harsh reality of your own projects.

Think of your projects like a ratchet for your understanding.

Here are some stages of difficulty and timeslines for your projects:

Baby stage (You've learned the basic syntax of one programming language)

- Build a crazily basic HTML5 Website (no backend logic, just a collection of HTML, CSS and Javascript)

- Build a "Hello, World!" mobile app

- Build a super basic command-line app

Here's a very early project from my own journey: A website to advertise my Grandma's house for sale.

It won a number of awards (no

it didn't):

Early stage (you've done 3-4 few baby stage projects)

- Todo list app

- tic tac toe

- v. basic web scraper (one page max)

- Create a one-page portfolio website for yourself

Mid Stage (you've done 3-4 few early stage projects)

Take what you learned in the early stage and apply it to something you actually care about. e.g. scrape data about chess scores if you're into chess, or about basketball scores if you're into basketball. But keep the feature set very tight. Make sure it's something you can complete in a weekend.

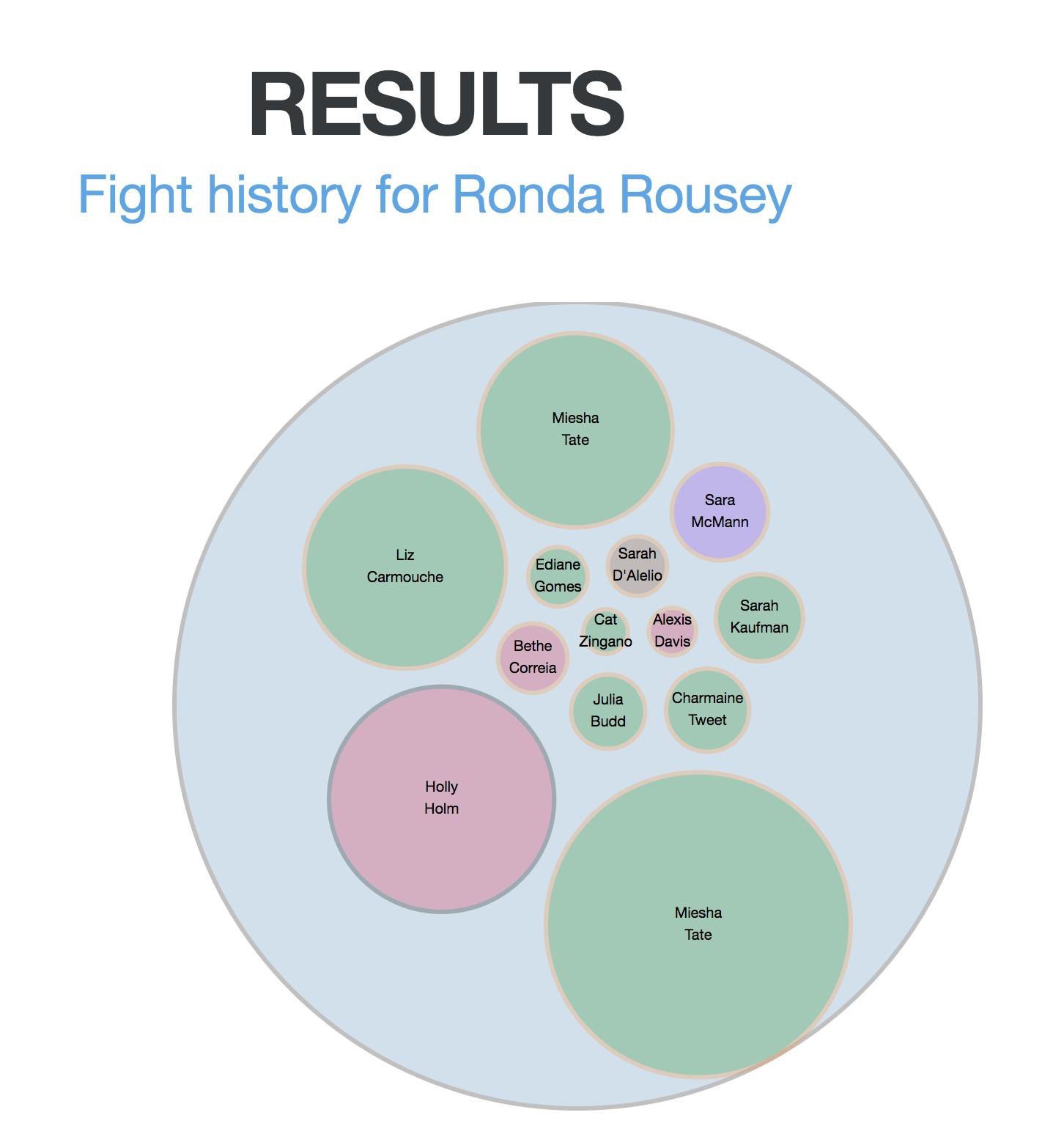

I'm an MMA nerd, so I made a site that showed fighter's records interactively which looked like this (was live

for many years but I've taken it down now):

Late stage (you've done 3-4 few mid stage projects)

Now you can take on something a bit more ambitious (don't go crazy though). Aim for something that you estimate will take you three weeks full-time, or two months part-time. A classic anti-pattern here is to pick something that takes way too long.

It's at this stage you'll find concepts starting to click. Here's an example of a stackoverflow question I asked seven years ago. To most professional engineers, this is a laughably stupid question - I've basically failed to understand how REST APIs work, but note that three days later I'm back to answer my own question. Do you think those three days were fun? Fun is not the term I would use. But I still remember suddenly understanding the concept to this day.

Late stage projects are where you will start to get a real feel for what software engineering is like. You won't be getting stuck on stupid things like incorrect syntax as frequently anymore. Late stage projects are also where you will learn how to debug - i.e. the process of identifying and fixing problems in your code. This is a skill that you should practice deliberately. Read up on things like how to place breakpoints in your code, and how to use the debugging tool in your language of choice.

Graduation projects

These are just what professional software engineers call "side projects", or Indie Hackers call "side businesses".

Each of these project stages should act as a skills ratchet. It is very easy to get stuck at a certain level (because you will enter a flow state and that is pleasant). You need to be spending a meaningful amount of your project time pushing yourself because flow does not lead to mastery, deliberate practice does.

Source: Scott H. Young's Blog

Learning Materials Along the Way

As you encounter problems in your projects, read blogs, documentation and tutorials about those specific problems. Because you then immediately put what you have read into practice (adapting the concepts to your apps) the learning value is much higher. For hard problems, like having no idea how a necessary framework is used, consider supplementing your project learning with a book or course, but make sure you don't use it as a procrastination crutch.

Yes, in some cases you will not know what you need. This is what your network is for (see next section).

Iterations

You want to get a lot of projects done. Finish your work. Unlike with reading, where abandoning a crap book half-way through is usually a good idea (as Patrick Collison has talked about), with software projects a lot of the complexity and final challenges emerge in the endgame - the last 10%. This is why projects in industry tend to get stuck at 90% complete. A great way to combat the urge not to finish is to make the site live or public. Get some traffic! And if it sucks, don't worry about it - you are still learning.

You'll worry less about what people think about you when you realize how seldom they do

-David Foster Wallace

Rabbit Holes to Avoid

- Attempting to pick up another language within your first year of coding - focus on getting good at one first

- Starting multiple projects at once - you will just be tempted to switch whenever you reach a hard point

- Not doing projects (i.e. just reading or watching videos)

- Doing the same project for ages

How Long Is This Going to Take?

How long is a piece of string? It really depends on you. If you're consistent, then you should advance to the "late stage" with about 6 months of part-time practice. Let's say about 10-20 hours of deliberate practice per week. Especially early on when you are still laying the foundations, if you take long breaks between learning sessions you will find yourself almost starting from scratch each time.

Shipping

You must ship. Put your projects in front of users. It will lift you up to the next level. It will motivate you. It will terrify you. Ship it. Done is better than perfect. Make sure you have read enough about things like LeanStartup and the customer development process

Personal Story

In my case, I studied outside of my day job as a business analyst for 6 months before I got a role as a junior front-end developer. However, I only did that role for 6 months because an opportunity to work in Beijing (not as a developer) came along and I realized that I could always go and work as a developer, but this was a rare chance to work in China doing interesting work. I then spent the next three years working on "graduate projects" outside of work. I probably built about 8 or 9 apps, but by far the two largest projects during this time were:

Here is a review of my first significant "graduation project":

- Digital Grappling This was a playable state diagram of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and ran for 4 years, had about 5000 users and made me about $200 per month for most of those years, until I eventually shut it down because it wasn't worth the time. Highlights included the first sale (the first time I ever made money on the internet), handling support requests for customers in California at 4am in Beijing, and the time when I realized that my hosting provider had been acquired and I had one day (turns out you shouldn't ignore certain emails) to move everything to new infra before the site went down.

Here's a review of it Here's an archive of the landing page

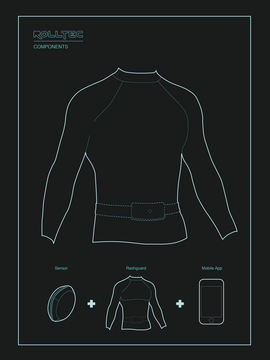

- Rolltec This was a wearable for martial artists. This project introduced me to machine learning, which in turn set me up for working as a machine learning engineer further down the line.

Here is the technical write up

Here is the failed kickstarter page

I credit this time with making me really sure that I actually wanted to be a developer. The fact that I was able to sustain my interest in coding for such a long period outside of work confirmed to me that I wasn't just "having a phase" or just wanted to try something different for a while. It convinced me that this was something I would really enjoy spending a significant chunk of my life working on. So after three years, I finally took the plunge and became a backend developer in London, and it's been quite a ride!

Part 6: Building Your Network

Communities

As you are progressing through your projects, it's important to talk to a mix of people about your approach and about tech in general. I am a big fan of meetups for this reason. Especially when you are not working in a technical role and are teaching yourself development outside of a tech bubble, then you need to find a combination of people:

- People who are much more advanced than you and can advise you on the metagame of progressing in your coding journey. Occasionally they might give you coding tips too - and those moments are to be cherished. I've benefited from advice from so many friends who have patiently explained basic things to me over the years. I think this is why online communities like stackoverflow are so helpful, we all remember what is was like to be a noob.

- People who are on a similar learning journey to you - this will provide you with motivation and people who will be willing to meet up on the weekends and try some pair programming (professional developers won't want to do this with you unless they are good friends).

- People who inspire you. Not everyone is willing to mentor and directly help. But sometimes it's enough to overhear someone talking about fixing some crazy sounding bug and to enjoy the fact that you understood some fraction of what was being said.

Get involved in these communities, even if you feel uncomfortable. I volunteered to run the Beijing Python meetup (along with the great and powerful John Dietrick) when I wasn't even working as a professional developer and was still pretty new to Python. This turned out to be incredibly rewarding over the years. Shout out to Evgeny who took it over from me and has grown it from strength to strength. Volunteer to give presentations of your work at small meetups, then gradually progress to larger ones as your confidence grows. Giving presentations and teaching others is a great way to solidify your understanding of concepts, this is the Feynman Technique

Outside of in-person meetups, it's a good idea to start posting your questions on stackoverflow

- don't forget to contribute back and try and answer some as you get more advanced. Learning the art of writing a good question (basically a good bug report), is very important.

Twitch is also now a great place to go and watch world-class developers at work. For Pythonistas, I'd definitely recommend former pytest core contributor Anthony's channel and you can find similar channels with great people from any programming community. Long-form twitch and youtube streams can be a great way to pick up tacit knowledge.

People are much more willing to help if they feel confident that you are ready to be helped.

Demonstrate this with detailed questions explaining what you have already tried, making it very clear that you are not being lazy.

Open-Source

The chances are that you are using open-source software. Read the source code! Learn what a well maintained project looks like. It's also worth checking out the "issues" on a project and seeing if there are any marked as "beginner-friendly" or doing things like writing documentation. This can be a great way to ingratiate yourself with some seriously talented programmers. Ideally, you want to pick not the most popular open-source projects, but more like "second-tier" projects which still have a strong community but might be struggling more to find contributors.

Paying for Help

At certain key points in your learning journey, pony up the cash for a proper code or project review. Just jump onto upwork or codementor, find someone who has been doing the thing you are trying to do for a decade and who has good reviews, and then sit down with them for an hour or two to get feedback. This might set you back $100, but it will be money well spent if you have put in the work to make sure your project is as good as you think it can be. You will watch with horror as they find countless areas for improvement. And those will be lessons you remember, because forking over your cash gets your attention. This is also critical for security audits of your site if you are handling real user data. I was smart enough to do this with my early projects and had a very worried looking developer point out to me that I might want to encrypt user passwords in the database!!! So obvious now, but when are starting out you don't know what you don't know - so get help.

Part 7: Getting Your First Software Engineering Job

Much has been written about this topic. The good thing about the project-based approach is that it doubles up as a portfolio you can send when applying to jobs, and also as something to talk through in interviews. This is yet another reason why shipping is critical - it gives you live apps you can point to and say "I made this". If it has users, even better. There are many (the majority I would say) professional engineers who have never launched an app of their own into the world. You can truly stand out from them.

That is about getting invited for interview. Then there is the actual interview, which is a pretty specific skillset in and of itself. You will need to revise data structures, algorithms and system design. I'd advise checking out companies that don't do whiteboard interviews. Also, don't beat yourself up about getting into a FAANG company for your first professional job - you can always look to do that on your next job hop. Having said that, try and get into a company where you have reason to believe that great engineers work. This will pay massive dividends as you will learn so much from your peers. Don't chase money - that comes later.

Do some mock interviews! If you've been networking away and attending meetups, hopefully by now you have met people who might be willing to do this for you as a favor. If not, just pay for a few practice interviews - there are many companies who will do this for you for a modest fee. What have you got to lose? And while you're doing that, record yourself. Do you feel like a jackass doing that? Well, do you feel like a jackass having an extra $10k in your pocket?

Key resources here are going to be:

- Cracking the coding interview - great overview of preparation steps and includes exercises and examples

- Hacker Rank for algorithm practice

- Read a couple of books on architecture and practice sketching some designs. A good starter is Fundamentals of Software Architecture

You want to make sure that you've got a "skeleton" project repo in your github that you can rapidly clone and adapt to do a few basic things like spinning up a web server, database migrations, creating a command line interface and the sort of typical coding tasks you might get asked to do in an interview. Practice doing this sort of thing against the clock. After every interview, make notes about what you got stuck on. Write up things that you wished you knew better. I remember an excruciating interview where I gave a crap answer about cross-site scripting which prompted me to write this blog post. To his credit, David Winterbottom was extremely patient with me during that interview, and that is something I always remember and try and pay forward when I am interviewing candidates.

You live and learn. Embarrassment can be a great teacher.

Part 8: Keep Growing and Getting Promoted

If you are self-taught, you'll probably feel some imposter syndrome during your first job. I don't think this ever completely goes away. You'll have to learn new languages, frameworks, and architectures, and each time you'll think "why am I struggling with this?" and the answer will be: "because as much as software engineers love to say that something is 'pretty straight forward' it never really is."

From here on out, the gains get smaller. It is the nature of learning a new thing that early in the process you can double the amount you know about the subject every week. This is because you know so little. As you gradually become competent, progress becomes incremental. Peter Norvig's advice comes to mind here about teaching yourself to program in 10 years. Things like learning a new language every year strike me as very good advice - ensuring that you do not get stuck in one area and too used to comfort.

You should treat your jobs like a paid apprenticeship. Now you are getting paid to learn how to program. I would argue that the three key benefits you get working as a professional project compared to your own projects are:

- Working on much larger systems, which teaches you about the importance of maintainability and architecture

- Working with large teams, which teaches you about software collaboration

- Working with large numbers of users, which teaches you about performance under high traffic

However, as the ever-wise Erik Dietrich says:

2-4 years is plenty of time to become as good at the general skill of “programming” as anyone needs to be.

Many of the hacker news crowd will howl with rage at this statement. Outrageous! Preposterous! Read the article.

The crux is that beyond a baseline, programming skill and getting promoted are not really that linked. If you don't want to get promoted and are happy to stay at a certain level then by all means keep coding. However, if you want to progress so that you have more autonomy and say in decision-making you should ensure you are growing other skillsets such as:

- Presenting and public speaking - volunteer to speak at small conferences. Befriend people who have done conference talks before and ask if they will introduce you to conference organizers and/or do a joint talk with you. This is what I did to get my first major conference gig

- Management - Cedric Chin's work is indispensable here

- Product Management (note that this is another reason why you should ship and get users - it will train you in product management)

- Design (I'm still working on this one)

- Negotiation - Patrick McKenzie's guide to salary negotiation is a must read

- Politics - you need to understand the game. Read Developer Hegemony, The Prince and The Art of War

In the vast majority of companies, executives look down on software engineers as effectively ditch diggers. To climb the greasy pole, you need to have your wits about you. Getting better at programming is barely a factor.

Alternatively, you can embrace Indie Hacking :) The good news is that now you have that option. You're capable of building MVPs for ideas you might have, or leading others to do so. You've been an engineer for a few years, you've built some complex systems. Now you have options. You can take time off and feel reasonably confident you can always get another job. This is a great position to be in.

The journey was hard and enjoyable. The journey continues much as it always was.

If you found this guide useful, please consider signing up to our mailing list, as we produce quality content on a regular basis